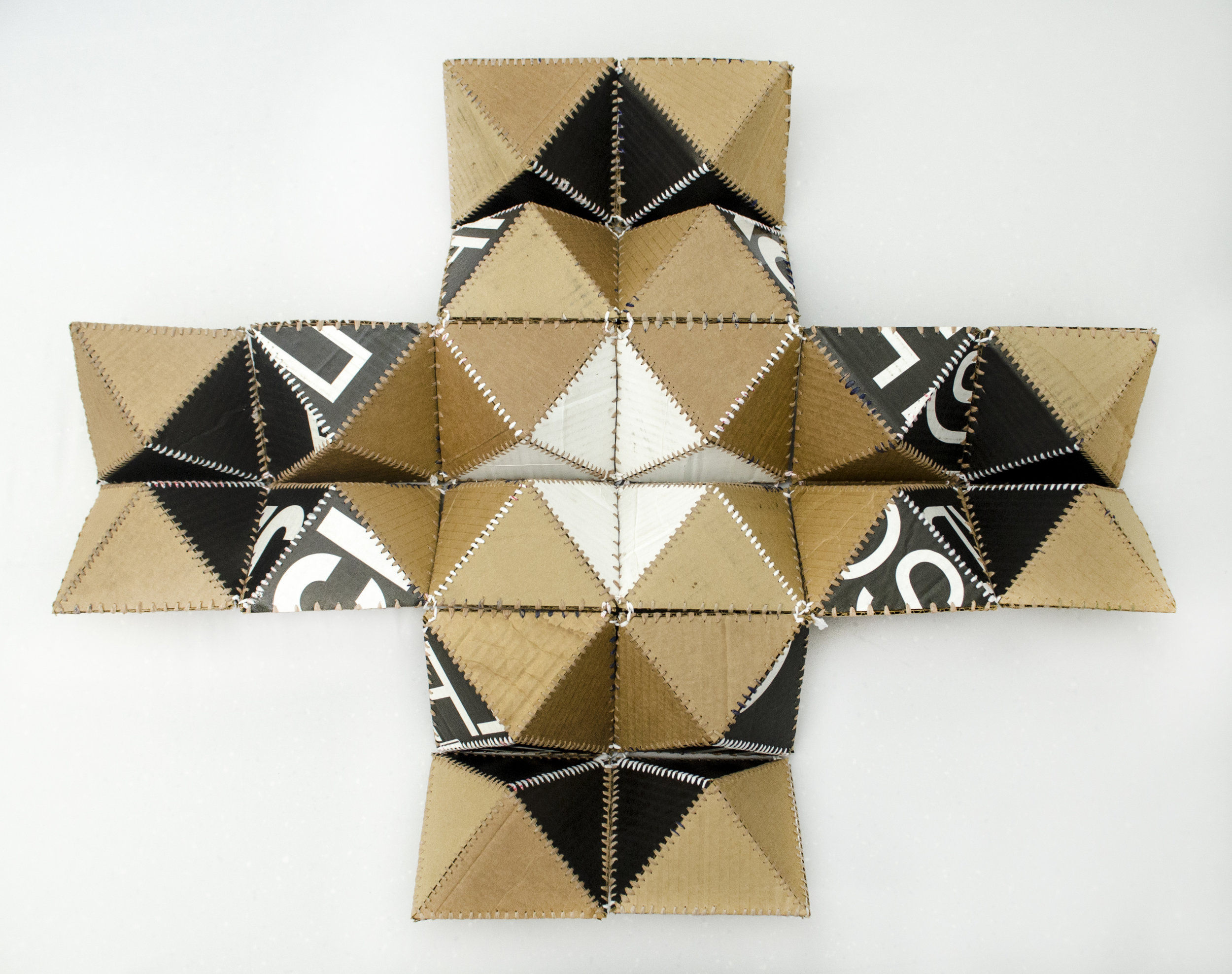

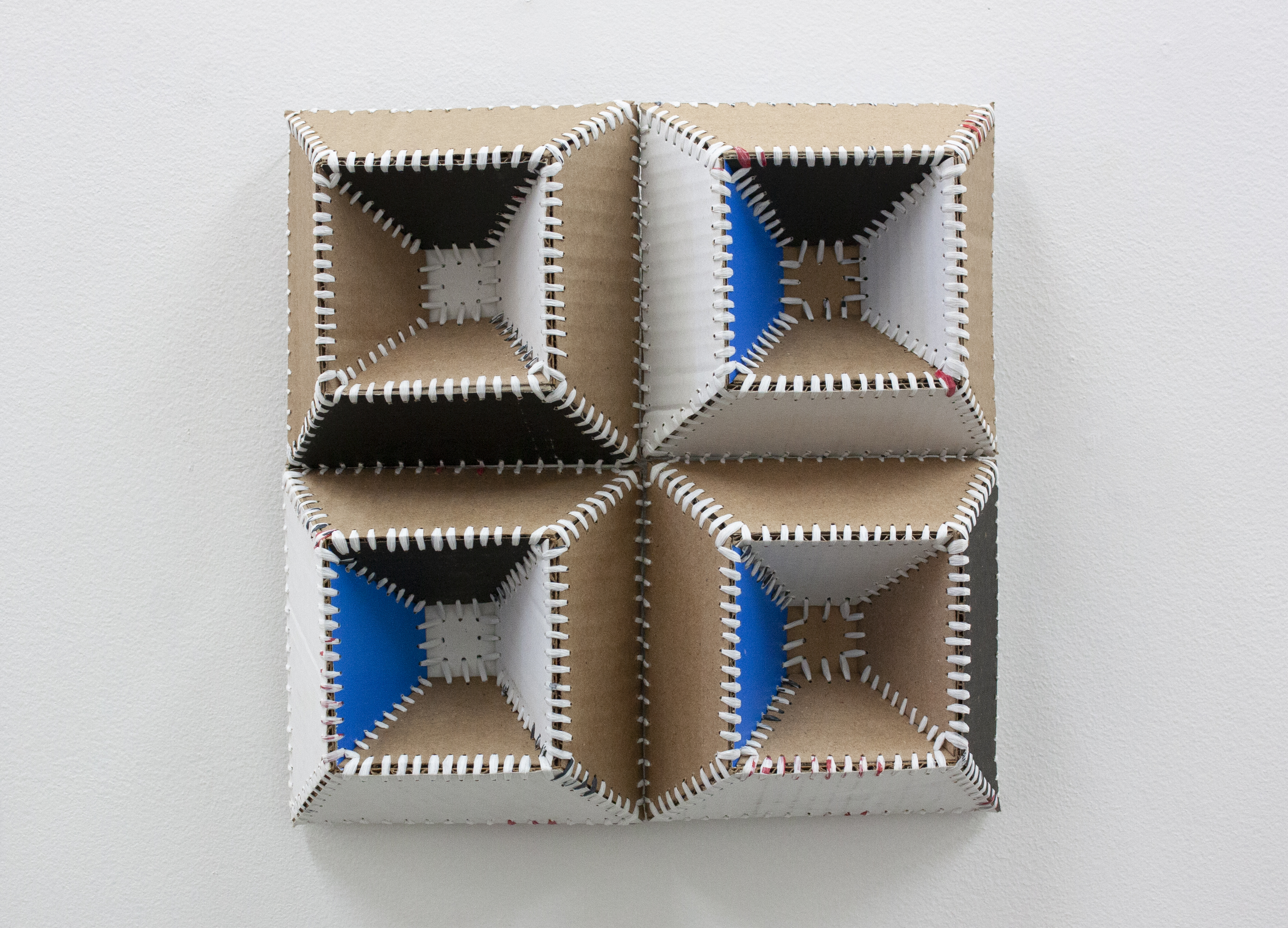

Helen O'Connor received her B.F.A. in Textile Design from the Savannah College of Art and Design in 2017. In 2018 she moved to Maryland to pursue a career as a thermal blanket technician designing, fabricating and installing insular blankets for aeronautic and spacecraft machinery. The flat pattern, 3D and kinetic design techniques evident in her quilts were largely developed during this period.

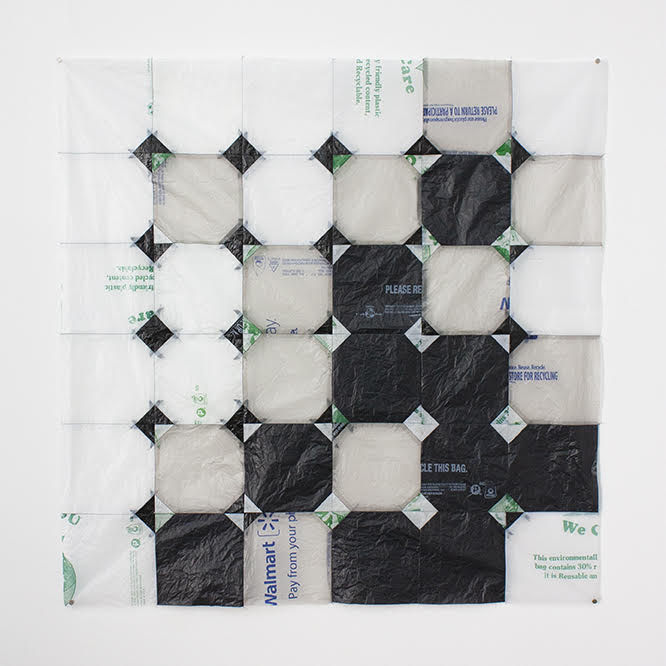

The quilt, symbolic of inheritance, comfort, class and salvage is a recurring theme in Helen's work. She endeavors to give new meaning and context to the traditional craft by reinventing its content and use.

Sibilla: What initially drew you to textile design and quilting? Was it something that you were interested in before SCAD or was it something you were introduced to during school?

Helen: My interest in textiles is such an integral part of my art practice that I often forget where it came from: camp. By the time I was seven I had a predisposition to working with my hands. I begged my parents to send me to my brother's sleep away camp, which promoted a non-competitive environment and a diverse program on traditional crafts. Over the course of eight summers, I learned about felting, tapestry and basket weaving, macrame, knitting, and quilt making. By the time I decided to apply to college my academic interests were incredibly specific: cloth and the hands that make it. I chose SCAD because it had the most exciting curriculum dedicated to fiber art. During orientation, the school president commented that we would learn not only about our field of interest but discover the existence of entirely foreign disciplines. She asked, to make a point, how many of us had chosen to study textile design. My hand was one of ten that rose in an audience of roughly five thousand. What can I say? I’m obsessed.

Sibilla: The popularity (or rather, unpopularity) of textile design and the fact that it is predominantly occupied by women seem to go hand in hand. The validity of disciplines generally categorized as “crafts” doesn’t seem to enter the realm of fine art until a man takes it there. What is your experience in regards to gender and textile work?

Helen: To use the term "craft" to describe art as naive and conceptually lacking is a contemporary phenomenon of art criticism. Whereas modern art was initially characterized by a willingness to experiment within a given field, the perceived success of the post-modern artist is largely based on conceptual creativity. Craftsmanship has endured a fall from grace as an anachronistic mode of true expression. I can't claim to hold any strong beliefs in what makes art "fine," but to participate in an artistic practice is to be at the mercy of the opinions of the viewer.

I've been called a sculptor time and again, though it's not something I'd ever call myself. I find significant meaning in the history and implications of textile design in my work, but to say so is enough to declare myself a spinster. The term "spinster," is a perfect example of how gender and workmanship can be weaponized to exclude some and celebrate others. I am spared these remarks at times because of the structural and geometric nature of my work, but as a result, it is generally assumed that I draw inspiration from male sculptors. I can't say it bothers me. For every viewer that evaluates my craft in relation to a man's influence, there is one who sees the invisible hand of countless generations of female artisans, stitching together a language by and for women. I am speaking for them.

Sibilla: There is an incredibly long and rich history of textile work. How do you see contemporary art, fashion, and design referencing the past?

Helen: Oh, all the time. This may in part be because of my interest and focus on textile history. As a result, I see it everywhere. For example, in 2015 I visited the Renwick Gallery in Washington DC to view their "WONDER," exhibition. I was overwhelmed by the visual influence of fiber techniques. Jennifer Angus' In the Midnight Garden is a floor-to-ceiling installation of dead insects arranged in designs mimicking embroidery. The walls themselves are painted with cochineal pigment, an insect native to Mexico, from which was derived the first and most coveted colorfast red dye. Patrick Dougherty's Shindig relied on basket weaving to erect natural architectural structures out of branches. Janet Echelman's 1.8 Renwick sculpture filled a 100-foot long room with hand tied netting. The netting, traditionally used in fishermen's nets, corresponds to a map describing shock waves released during the Tohoku earthquake.

Textile history can largely be considered human history. The invention of string marked the development of survival techniques we still use today (building fires, hunting, fishing, and creating cloth). Fabric was a reliably valuable item of currency, a utility we continue to see in the exchange of the modern dollar. Garments are visual identification of social hierarchy.

I could not separate my knowledge of fiber art from the foundational textile techniques upon which all of these pieces were based. In my mind, they were one and the same. I am delighted to see it everywhere I go.

Sibilla: When you went to work for Aerothreads (a thermal blanket consultancy), what skills or insights did you bring to them as an artist and vice versa, what skills from that job transferred over to your artistic practice?

Helen: Multi-layer insulation (MLI) blankets act as a protective barrier installed on both the inside and outside of spacecraft machinery. Its purpose is multifaceted: maintain temperature limits, redirect static charges, absorb or reflect light and radiation, and shield delicate hardware from harmful debris. All of this needs to be done with minimally invasive blankets that blend seamlessly with every feature of a spacecraft.

Due to the incredibly strict parameters around building thermal blankets the only way to make them is by hand. Each blanket is composed of layers of polyester and polyamide, often coated in different types of metal. Folding this material can crumple, compress and ruin the effectiveness of it, so a fabricator must be diligent in forming a blanket perfectly.

I knew none of this when I applied to work at Aerothreads, but that had very little to do with my eligibility for the job. All of my colleagues were artists: costume designers, screen printers, quilters, and sculptors. My experience transforming flat patterns into 3D designs and working within the mathematical limitations of quilting are what landed me that job. During my time as a Thermal Blanket Specialist, I developed a commitment to precision, broadened my knowledge of material application and learned fabrication techniques that I still use today.

People were often shocked when I told them what I did for a living. It is hard for many to imagine a practical application for artistic skills outside of an artistic setting. By the time I left, I was fully confident that my abilities did not limit me to working within a set number of industries. The most satisfaction I received from this position didn't come from any singular launch project, but in knowing that my craft had become my intuition.

(Images and artist bio courtesy of the artist).